Time to move on from ‘cash-plus’ investing?

Artemis’ Head of Fixed Income Stephen Snowden says the labelling of many absolute return funds no longer makes sense: if a fund has a positive yield from its fixed income exposure, it is a mathematical certainty that it is long the market, meaning it cannot be an absolute return fund.

It would, if you’ll forgive the pun, be wrong to state in absolute terms that ‘cash-plus’ investing is dead. But results from its recent health checks haven’t been encouraging.

The Target Absolute Return sector grew to become the third-largest IA sector by assets under management from 2016 to 2018. Today, however, it has slumped down the rankings to thirteenth place1. Of course, not every fund in the sector has a cash-plus performance target – but many do and it is clear that demand for them has waned considerably. The slow demise of Abrdn’s GARS strategy explains part of this downward trajectory, but by no means all of it. So what went wrong?

IA Target Absolute Return Sector AuM £ bn

Rise and fall: the decline of the IA’s Target Absolute Return sector reflects the challenges of cash-plus investing

Cash-plus investing is a worthy quest. For many investors, the prospect of a return greater than a savings account in exchange for slightly higher volatility is an attractive proposition. Sadly, consistently delivering on that promise through different market conditions has proven to be extremely difficult.

The challenge for fixed-income investors in attempting to deliver cash-plus returns is even greater, particularly after the re-set in bond yields. The reason is simple: shorting bonds is expensive.

The bond market is not a 50/50 bet

A quick refresher of some bond basics: own a bond and you receive income. Equally, if you short a bond, you’ll be constantly paying out income. So, while you can make money by shorting bonds, time is always against you: every day you are short you will be haemorrhaging cash. If you are short, not only do you need the market to fall you also need to pray that it falls quickly – or your capital gain will quickly be overtaken by the income you’re paying out. It is much more comfortable to be long bonds and simply harvest their income. If you are long and the market is stable, you win. And if you are long and the market goes up, you win… big.

Prior to the financial crisis, when yields were ‘normal’, very few fund managers attempted to outrun this financial inevitability. Not many absolute-return bond funds existed. But as yields fell, the odds from shorting improved: the lower yields got, the cheaper it was to go short. The number of offerings grew rapidly. But if absolute return bond funds didn’t really exist a dozen years ago when yields were last at these levels, do they make sense today? For the following reasons, I would argue not.

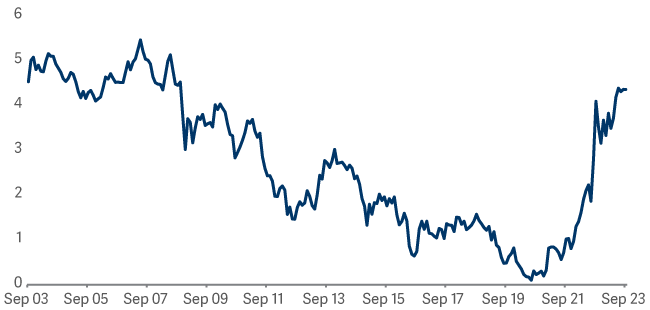

10 year Gilt yield

Back to normality: the cost of shorting bonds has returned to levels last seen more than a decade ago

I’ll not bore you with the mathematics, but the higher bond yields go, the more their ‘modified duration’ goes down. Put simply, capital volatility falls as bond yields rise. So absolute return bond funds have been served a double whammy. Not only has their cost of shorting increased, but the scale of capital gains they can earn by shorting has fallen.

Reflecting that reality, most ‘absolute return’ bond funds today actually generate a positive yield; so they are not, strictly speaking, absolute return funds at all. Most investors know and accept that – and there’s nothing wrong with that positioning. But the labelling simply no longer makes sense: if a fund has a positive yield, it is a mathematical certainty that it is long the market; it cannot be an absolute return fund.

ICA BofA Sterling Corporate & Collateralized Index

Double whammy: the sharp fall in modified duration has dramatically reduced the potential gains from shorting bonds even as rising yields have pushed the cost of shorting higher

Before the global financial crisis, most fund managers and most investors did things the simple way: they owned bonds and harvested their income. Then, for a decade or so, quantitative easing created a world of ultra-low bond yields. The low cost of shorting bonds made it seem a reasonable response to unreasonable market conditions. Yet that world is over: we are now back to ‘normal’. An approach that might have made sense when 10-year gilts yielded almost zero simply doesn’t when they yield 4%. The concept of shorting or hedging is not dead. But why constantly bet against the odds? Why keep swimming against the tide? Today, cautious investors can simply enjoy the income that has returned to bond markets.

The case for going back to the old ways is compelling. Cash-plus investing is not dead – it is merely giving way to something better-adapted to the world as it is today, rather than the world as it was for most of the last decade.