When high yield doesn’t mean high risk

Jack Holmes, manager of the Artemis High Income Fund, says that in an environment of persistent inflation, the risk/reward trade-off in shorter-dated high-yield bonds is more compelling than in government debt.

When high yield doesn’t mean high risk

As I sit down to write this, US CPI has jumped from 3% to 3.2%, bucking the trend of monthly declines we’ve seen over the past year. While only a small increase, we believe this highlights just how difficult it will be to bring inflation back to the Fed’s 2% target.

Had the rate of inflation continued to fall, many strategic bond funds would have profited from their long duration, government-bond heavy portfolios.

Artemis High Income is not one of them. While we thought it unlikely that inflation would return to the high single digit levels of last year, we expected it to remain persistent. With this in mind, relying on long-dated government bonds made no sense.

Instead, we thought there was a much better risk/reward trade-off in shorter-dated high-yield bonds. July’s inflation reading has only strengthened this view.

Balance of power

There are two key metrics to focus on when analysing the balance sheet strength of high-yield bonds. The first is net leverage, or the ratio of debt to earnings – the lower, the better.

The second is interest coverage, or the number of times that earnings cover interest bills. Here, the higher, the better.

While high-yield bonds are typically regarded as the riskiest area of the fixed income market, both measures would suggest the sector is currently in a strong position.

Focusing only on the BB and B rated part of the market, where we have around 50% of our fund invested, the picture becomes even more encouraging. Margins in these areas have already returned to their pre-pandemic averages.

It is a different story for CCC-rated debt. Bonds of this quality tend to have structurally lower margins than their higher-rated counterparts. They are also more cyclical, which is why those margins tend to fall even further during downturns – and, on the whole, have yet to recover from the pandemic. Together with a higher cost of debt, we think that CCC-rated bonds are the one part of the high-yield market that looks excessively risky. Hence, bonds of this category now make up less than 2% of our portfolio.

Rapid pace of balance sheet repair

The good news for investors who are unwilling to take excessive risks with high-yield bonds is that the quality end of the market is expanding, creating a wider universe of opportunities to choose from.

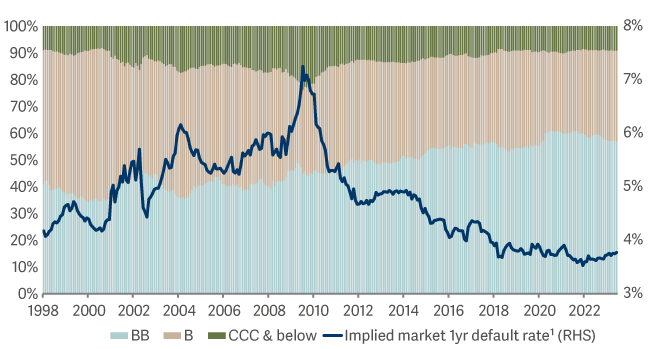

The chart below shows that BB-rated bond’s market share has risen from about 40% since the financial crisis to about 60% today. Over the same time, CCC-rated debt has fallen from about 20% to 9%.

Increasing quality

Highest quality part of the market - BBs - have significantly increased their share of the market

On the face of it, an 11% fall over 13 years doesn’t seem like such a large move. Yet the implications for investors are enormous.

Historically, the chance of a BB-rated bond defaulting on its debt has been 0.6% per annum. This rises to 25% for a CCC-rated bond – almost 50x as much.

Building on scepticism

UK housebuilder Miller Homes is a good example of the sort of value currently available towards the upper end of the high-yield market.

It builds about 4,000 houses a year with an average selling price of £300,000, focusing mainly on the central belt in Scotland, the northwest of England and the Midlands.

These houses tend to be for people who want to make the step from their first home to their second, looking for more space, for children for example.

Miller Homes’ bonds are currently trading at about 79p in the pound. This is significant as although we’ve seen a lot of enthusiasm in the market over the past 12 months, the price of these bonds hasn’t moved at all over this period. It is also yielding 12%, which reflects concerns in the market that we think are exaggerated.

The first of these concerns is materials inflation, which is pushing up housebuilding costs. However, we estimated that the company only needed to raise prices by 3% to account for the increase in costs over the past 18 months – which it has managed to do comfortably.

The second is mortgage availability. Again, we don’t think this will be a problem, as the company is not selling to first-time buyers who are trying to scrape together a deposit, but to people who have already built up some equity in their home. Banks are also eager to ‘green’ their mortgage book, and the only way to do this is to lend against more new-build houses, which have better environmental characteristics.

We are not too concerned about a fall in house prices, either, as Miller Homes doesn’t typically build in ‘bubble’ areas with elevated valuations, but in those that have traditionally been undersupplied.

Combining their inventory of finished houses and the value of consented plots, then subtracting the value of building those houses, the loan-to-value on the company’s bonds at today's cash price is just over 20%, meaning you will need to see an exceptional fall in house prices for these assets to be materially affected.

Of course, these concerns may turn out to be justified. Interest rates could rise further, which wouldn’t be good for a property company. But it could be even worse for a long-duration bond. We don’t know which one will prove to be the better investment, but at least with Miller Homes we are getting paid 12% a year while we wait to find out.