Ignore the instability in the mortgage market – the UK consumer is on solid ground

With only about 30% of households in the UK with a mortgage and a larger proportion owning their home outright, we believe the UK consumer is in better shape than headlines would suggest.

The word mortgage literally means ‘death pledge’, and while the ‘death’ part of the phrase originally referred to the way in which the pledge would only be considered finished once the debt was repaid, anyone who has recently moved from a fixed-rate loan of this type onto a tracker product could be forgiven for feeling an impending sense of doom.

If you find yourself in this situation, the thought of investing any spare cash is likely to be at the back of your mind. And, if possible, the thought of investing in the UK consumer is likely to be even further behind. But it’s always worth looking past your own personal experiences and emotions when making investment decisions. A small amount of analysis suggests the impact of interest rate rises on the UK consumer will be more muted than newspaper headlines would have you believe.

Only about 30% of households in the UK have a mortgage. A larger proportion own their home outright. Meanwhile, a significant number of homeowners fixed their mortgages when rates were low, meaning it will take time for the impact of monetary tightening to filter through. While the Bank of England base rate stands at 5%, the average figure paid by a UK mortgage holder is just over 2.5%.

Admittedly, these are repricing upwards at 6-7bps each month, meaning that while interest rates currently represent a small headwind to the UK consumer, it is one that is gathering momentum.

Just 2.5 months ago, the average five-year mortgage stood at about 4.5%. Given where swap rates are today, we’d expect new fixed-rate mortgages of this length to settle between 5.5% and 6% in the coming months.

UK households on fixed-rate mortgages that will refinance in 2023 at a rate of 4.5% will pay an additional £10bn of annual interest – money that won’t be spent in the economy – compared with today. At 5%, that figure rises to £12bn, while at 5.5%, it’s £14bn. And that’s not just for this year: we will see a similar headwind for households re-financing in 2024 and the first half of 2025, by which point the UK mortgage book will have largely priced out the exceptionally low interest rates of the past decade. Whilst this is a significant repayment shock for the households involved, this will be partially offset by a combination of principal repayments and elevated wage inflation since the mortgages were last refinanced.

But in aggregate, it is not all bad news for the UK consumer – firstly, the rise in mortgage rates will be partially offset by the falling gas price, with utility bills set to be £10bn lower this year than last if energy costs continue to fall. Secondly, the rise in interest rates will also benefit the pool of savings in the UK, which is far larger than the pool of mortgages, meaning anyone with cash in the bank and no debt to service will be better off in nominal terms.

This helps to explain why the UK economy has surprised to the upside. Whereas in November, the Bank of England was predicting we would enter one of the longest and deepest downturns since the war, today the forecast is that we will avoid a recession completely. Unemployment is expected to remain low, while take-home pay is rising. This is reflected in improving consumer confidence, which should feed through to a reduction in the savings rate – this currently stands at 8.5%, compared with a typical level of between 4 and 6%, and every 1 percentage point fall in this figure should equate to an additional £15bn of consumer spending.

The resilience of the economy is reflected in recent strong numbers from retailers, airlines and pub and restaurant stocks. Next is one example. Simon Wolfson is a prudent CEO and not the type who will hurry to readjust profits guidance upwards, yet just a couple of weeks ago, he did exactly that.

Obviously, you can’t ignore the impact of bond yields on equity prices. However, in a world where low interest rates have caused the majority of equity markets to substantially re-rate over the past decade, the UK equity market has de-rated. Take, for example, HSBC – a global bank listed in the UK. Today its P/E ratio is just over half its level in 2011 – when medium-term interest rates were last at similar levels – while its prospective dividend yield of over 7.5% is more than double. For stocks with exposure to the UK domestic economy, the discount is often even greater.

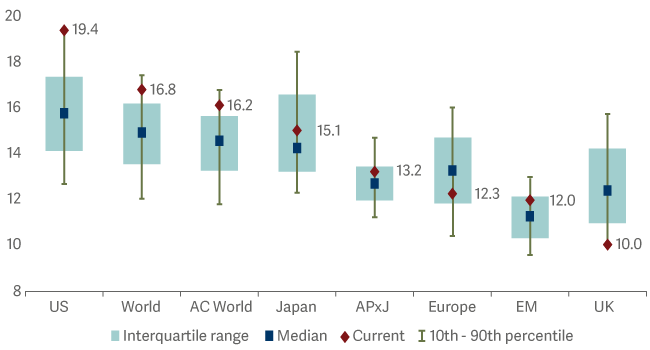

The UK equity market is trading at valuations well below historical averages

Remember, the FTSE All Share delivered the highest return of any major regional index last year, and its low relative value compared with the rest of the world leaves it well placed to continue to recover the underperformance seen relative to global markets over the last decade.

Unlike the word ‘mortgage’, there is nothing half-dead about the UK market – if anything, it is only sleeping. It might be a good idea to invest before other people wake up to its potential.