Hedged & wedged: The hidden danger in credit market derivatives

Credit default swaps offer a cheap way for bond managers to change their asset allocation when liquidity is squeezed. However, Head of Fixed Income Stephen Snowden warns that anyone using these instruments to reduce risk may find they end up doing the opposite.

Credit default swaps (CDS) are financial derivatives that were originally created as a type of insurance to be used by banks: a way to transfer large counterparty risk – or disperse the credit risk of lending lots of money to a specific company – to various other lenders. The lender would buy a CDS from a third party who would reimburse them if the borrower defaulted.

These instruments were designed to reduce risk. But what typically occurs with derivatives over any length of time is they become a market in their own right. For example, the most liquid CDSs today are parcelled together to create a broad index of investment grade or high-yield companies.

CDS indices are extremely popular among fund managers as they allow them to add or remove risk from bond portfolios. Some fund managers also use CDS indices to help asset allocate from investment grade into high yield and vice versa.

Lower liquidity levels are here to stay

The key advantage of the CDS market is its liquidity. These instruments can be traded quickly in large size, something that is much harder in physical corporate bonds.

At about $300 trillion, the bond market is more than twice as large as the stockmarket1. Yet despite its size, it can still throw up liquidity problems, particularly in corporate bonds.

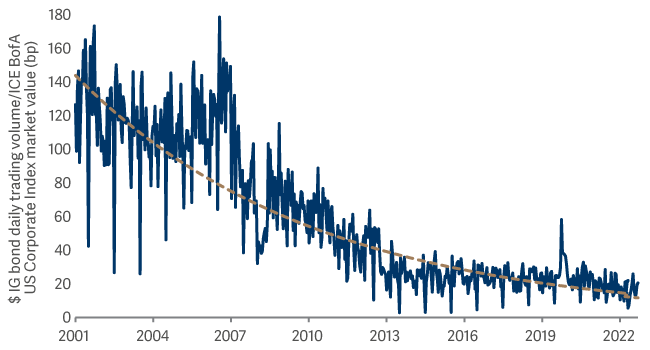

The graph below shows that the volume of trades relative to the size of the market has plummeted since the early years of the millennium, when many strategic bond funds were launched.

IG corporate bond trading as a share of market outstanding

This means that while it is still possible to move in and out of high-yield or investment grade bonds, doing so quickly results in unacceptable transaction costs. Therefore, fund managers have tried to find other ways to add or subtract risk quickly.

Derivative overlay

One method used by some of our peers is to use a derivative overlay, allowing them to increase or decrease high-yield or investment grade exposure without the associated expense of doing this with physical bonds.

Now, while this sounds like the perfect solution, there is one small problem – there are occasions when not only does this not work, it actually multiplies the risk.

The reason is that while the physical bond market and the synthetic CDS market are closely correlated in the long term, there is often a huge disconnect in the short term. This is known as basis risk.

This disconnect tends to be at its most extreme in times of volatility – exactly when you need your ‘hedge’ to work. This can be seen in the two graphs below.

The first shows the performance of the physical ICE BofA Euro Corporate index (LHS) and the synthetic Markit iTraxx Europe (CDS) index during the eurozone sovereign debt crisis.

In 2011, bond yields rose quickly on fears that peripheral eurozone countries, most notably Greece, would be unable to meet their debt obligations. There were even fears that financial contagion would lead to the breakup of the euro2.

When president of the European Central Bank Mario Draghi declared he would do “whatever it takes” to save the euro, this instantly stabilised the market. However, CDSs reacted much quicker than physical corporate bonds.

Hedged and wedged

Euro crisis Pandemic

The same thing happened during the pandemic. Both indices sold off aggressively at the same time, but when the Federal Reserve and other central banks announced a co-ordinated package of quantitative easing, the synthetic market rebounded far quicker than the physical one.

What’s the problem?

So why is this a problem? The reality is that the vast majority of investors cannot short physical corporate bonds, but they can short the CDS market.

In a risk-off environment, fund managers who want to reduce risk can't sell their bonds because the market is so illiquid. Instead, they will hold these positions and short CDSs, a strategy that is likely to work very well for them – until there is some good news.

When that day comes, they will find themselves long an asset that is doing nothing and short an asset that is rallying aggressively. That is basis risk. The nickname in the market is ‘hedged & wedged’.

Now, full disclosure: we do use credit derivatives. We use them frequently in the Artemis Target Return Bond Fund and occasionally in the Artemis Strategic Bond Fund. But, where possible, we resist the urge to use them as a ‘hedge’ to reduce risk as this is where they become dangerous: ultimately, there's no better hedge than selling the underlying asset.

Red flags

Be wary of a message along these lines: “Yes, the corporate bond market isn’t that liquid, but we own a portfolio of bonds we like and layer a derivative overlay on top to add or subtract risk and to asset allocate between high yield and investment grade.” It’s a neat message, but a careless one.

There are many ways to increase and reduce risk within bond funds, but using credit derivatives is one of the worst ways of doing it. Basis risk is unpredictable, but inevitable. That is why fund managers who find themselves long credit risk by owning physical corporate bonds and short CDS indices are referred to as being ‘hedged & wedged’.