Does ‘fund yield’ tell the full story?

The yield-to-worst figure that bond funds are obliged to present to investors is a blunt instrument that fails to capture the income or total return opportunities currently available in the high-yield market, according to David Ennett.

It feels at times that bond funds try their best to put you off. There are many versions of a simple concept such as ‘yield’ that investors need to wade through to get an idea of how a fund stacks up in terms of return potential.

One we use often in high-yield investing is the yield-to-worst, a phrase that does little to dispel bond managers’ reputation for being pessimistic.

According to Artemis’ carefully worded, compliance-approved definition, it “reflects the lowest potential yield based on the current price of securities within the portfolio under the assumption there are no defaults”.

Essentially, it is saying that while there are a range of potential return outcomes for every bond based on when they are called, we are going to assume that they all mildly disappoint and return the minimum in every case.

Not the most compelling call-to-arms for the asset class, but surely a sensible approach at least. If you are wrong, let it be that you made a bit more than expected. At present, the ‘yield-to-worst’ on the factsheet for our global high yield fund stands at 7.79%1 under this most pessimistic of scenarios.

Following the reset in global yields over the past two years, most bonds are trading below par ($100). This is unusual in a market that has historically traded at, or just above, par. The use of ‘yield-to-worst’ has generally been a good indication of the actual yield on a high-yield bond fund, but of late it is at odds with what we are seeing in the market.

The ‘actual’ yield

Unlike with investment grade debt, high-yield bonds can be ‘called’ or redeemed before they mature. This usually takes place between one and three years ahead of the redemption date, at a cash price of 100 – although this can be higher.

There are three reasons why high-yield issuers call their bonds early, which have nothing to do with the cost of their debt:

- Bank facilities (such as overdrafts and revolving credit facilities) normally have provisions around current ratios (current assets divided by current liabilities). Bonds that enter the final year until redemption become current liabilities, pushing current ratios outside the limits of what banks are comfortable with. Hence the need to keep longer-term debt at more than 12 months to maturity.

- Liquidity considerations are a focus of ratings agencies, which view high-yield issuers unfavourably if they fail to repay/refinance a bond well before it reaches the final year of its life.

- Corporate management prudence – high-yield companies are more reliant on markets being open to refinance any issues that are close to redemption. This means chief financial officers don’t want to let bonds get too close to their maturity and be exposed to market conditions on a specific date in the future.

Early calls are not a sporadic occurrence. Research from the Bank of America shows that over the past 12 months, high-yield bonds have on average been called more than 1.3 years ahead of maturity. This figure has stood between 1.1 and 1.8 years over the past decade.

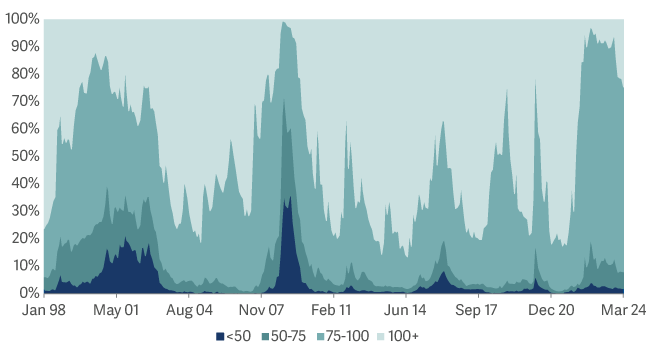

Today, there are more bonds trading below 100 – meaning there is more upside to being redeemed at this cash price – than at any time in the past 25 years outside of the Global Financial Crisis or the bursting of the Dotcom Bubble. But with bonds being called early, holders are receiving a further boost to yield and total return that is not being reflected in yield-to-worst figures.

ICE BofA Merrill Lynch Global High Yield Constrained Index price splits (% of face value)

The impact on total returns

For an example of what this means in practice, let’s look at a 6.5% 10-year October 2025 bond issued by Australian mining contractor, Perenti.

For much of the second half of 2023, the bond was trading slightly below par, at $98.5, and this is the price we added to our positions at. At this price, its yield-to-worst stood at 7.41%, while its spread was 310bps over US Treasuries. This yield-to-worst figure assumed that the bond would be outstanding until its final maturity in October 2025. A decent yield for a very strong high-yield issuer, but not much more than that.

In its August 2023 earnings call, Perenti’s chief financial officer said: “Our US dollar high-yield bonds mature in October of 2025, and thus we’ll be looking to refinance prior to them going current, in October of 2024.” The company had clearly announced its intention to call the bond at least 12 months early because it didn’t want it to ‘go current’, or become a short-term liability.

In this early-call scenario (in which the bond would be called at 100 in October 2024 rather than October 2025), investors could now expect a yield-to-call of 8.55% and a spread of 423bps above US Treasuries. Yet the official yield-to-worst figure was stuck at 7.41% because it was still, in theory, the lowest yield you could get. We were then in the position where we had to report a yield figure to worst that we were all but certain was worse than the one we would actually receive.

In the event, the company chose to call half of the bonds even earlier, in April 2024, and at a premium of 101.752. This meant it paid investors more than the amount outstanding and in addition, its new debt was actually more expensive than the debt it was retiring.

This resulted in an annualised return north of 14%2 on the debt being retired; a far cry from its 7.41%2 yield to worst. It may seem crazy to pay a premium to roll into more expensive debt, but it simply shows that corporates are very prudent in managing their debt and active investors can exploit this.

On a side note, you may be surprised to hear that when Perenti’s chief financial officer made his announcement, effectively telling the market the bond was undervalued, this didn’t move its price. This is because large areas of the global high-yield market are completely inefficient.

We’ve explained why in a separate article – the reasons are many, varied and really quite confusing, and let’s face it, you’ve probably had enough of that from high-yield bonds for one day.