Four themes that could change the outlook for global bonds

How should investors position strategically in the current volatile environment? To tackle this question, Liam O’Donnell, who leads the Artemis fixed income team’s strategy on macro and rates, outlines four key macroeconomic themes he expects to shape the fixed income market.

It is difficult to remember a time when the geopolitical landscape was in such a state of flux. Donald Trump in his second term is proving to be even more unpredictable and bold in policy announcements than in his first. Global leaders are turning to extraordinary actions in response – think Germany’s fiscal package or Canadian protectionism – as they scramble to grab a foothold in the new world order.

There are four key themes I am currently watching that could have a significant impact on global government bond markets:

- What is the trading range for 10-year US Treasuries?

- Will Japan continue to hike rates when other central banks are cutting?

- Will bond markets punish the UK chancellor in October?

- How should we play the end of the European cutting cycle?

1. What is the trading range for 10-year US Treasuries?

Economic conditions in the US do not appear conducive to further interest rate cuts, at least in the short term. I would summarise the US economy as follows:

- Growth is around trend

- Inflation is above target and unlikely to return to target over the next 12 months

- The labour market is resilient, with tariff shocks and reduced immigration partly responsible for weaker non-farm payrolls growth; there are few signs of companies shedding workers

However, it seems likely that Trump will succeed in bringing in a more obedient Federal Reserve chair and will get the lower interest rates he’s been asking for in 2026 (with or without the necessary economic conditions).

It is difficult to overstate just how important this could be for markets.

Should the Federal Reserve begin to cut interest rates without clear signs of inflation returning to target, then I would expect longer-dated Treasuries to come under pressure. It would almost certainly add to inflationary fears.

In this scenario I could see 10-year US Treasury yields quickly moving above 5% and I would be happy to trade 10-year Treasuries in the 4 to 5% range for the next 12 months.

2. Will Japan continue to hike rates when other central banks are cutting?

The Bank of Japan opted to hold interest rates at 0.5% on 31 July. I believe this ‘wait and see’ approach is inconsistent with the realities on the ground in Japan, where wage growth and inflation are still rising.

Japan’s largest trade union group, Rengo, secured the biggest pay increase since 19911 during this year’s annual wage negotiations. Additionally, a 6% hike to the minimum wage has been proposed2, which would be the largest ever.

At the same time, food prices are rising rapidly. Rice prices have almost doubled in the past year3, which will probably lead to higher consumer inflation expectations and continued upward pressure on wage demands.

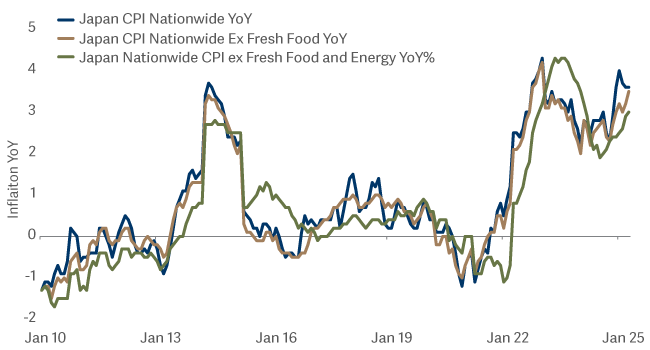

Japanese inflation

The Japanese government is intervening to help consumers through energy subsidies and by moving to unlock emergency reserves. So while wage agreements are coming in at all-time highs, the government is also directly subsidising consumption.

In the Artemis Strategic Bond Fund, we remain short 10-year Japanese government bonds because we think the Bank of Japan is behind the curve on inflation and wages.

3. Will bond markets punish the UK chancellor in October?

In my view, tax hikes in Chancellor Rachel Reeves’ Autumn Budget are inevitable.

For gilts, higher taxes are a double-edged sword. All else being equal, tax hikes lead to lower growth, raising the possibility of more interest rate cuts from the Bank of England, which would be supportive for gilts.

However, the government’s recent U-turn on welfare reform and the winter fuel allowance show that its willingness to rein in spending is low, sending a worrying signal to markets.

To add insult to injury, the Office for Budget Responsibility admitted it has been over-estimating productivity in its growth forecasts (which had been giving the chancellor extra fiscal headroom).

Higher taxes should lead to increased revenues, unless growth weakens so much that the tax take falls, in which case I expect the government would be forced to issue more debt.

After a period where the UK has suffered from international loss of confidence following a few disastrous Budgets for gilts, I continue to believe a successful delivery of both monetary and fiscal credibility would make the UK an attractive destination in an uncertain global environment. If Reeves does deliver tax hikes in her October Budget and restore credibility (the jury is still out on whether she can achieve this), then UK government bonds would offer great value.

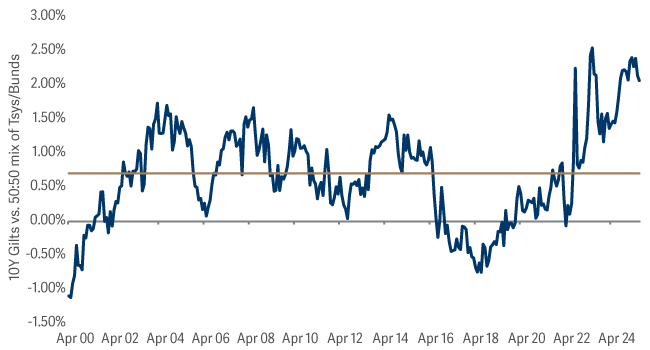

Gilts screen cheap against Treasuries and bunds

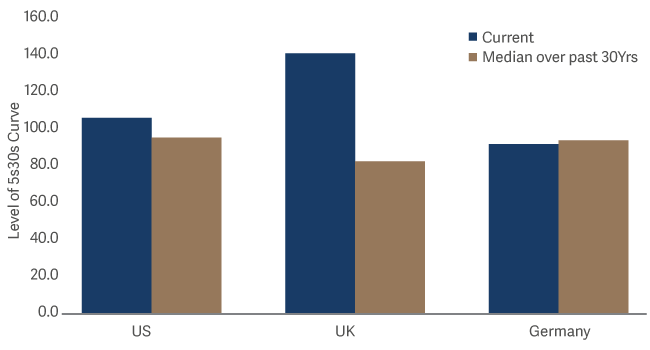

Not only are gilts cheap, but the gilt curve is steeper versus its own history than both US Treasuries and German bunds.

Current yield curves vs historical average

Against this backdrop, cross-market strategies (going long gilts and short other nations’ bonds) are beginning to look attractive, given that other government bond markets appear to be under greater pressure than the UK’s. I would argue that fiscal policy is more of a threat to German bunds and inflation is more of a risk to US Treasuries.

At this juncture, perhaps Reeves has given the market little reason to believe in UK PLC, however it is also worth asking how far gilts could possibly underperform over the next three-to-five years considering current valuations.

4. How should we play the end of the European cutting cycle?

After making eight quarter-point cuts, the European Central Bank (ECB) held its deposit facility rate at 2% in July – its first pause since June 2024. I think the ECB is likely to remain on hold for the rest of 2025 (barring significant shocks) and I expect EU bond yields to drift higher towards the year’s end.

From a policy perspective, the July meeting suggests neither complacency nor a rush to ease. I believe enough monetary easing has already been delivered, in conjunction with a renewed fiscal push, to stabilise EU growth and inflation going forward.

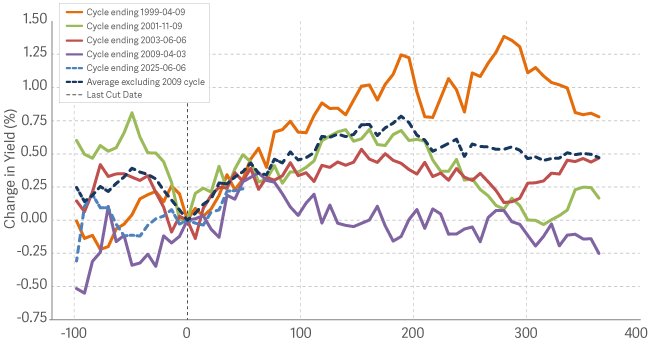

If I am proved right and the EU cutting cycle really is over, this would lead to higher 10-year government bond yields, if we let history be our guide. To illustrate this point, I looked at historical cutting cycles when the ECB was on hold for at least 12 months after the last cut (1999, 2001, 2003 and 2009) and charted what happened to 10-year German bund yields.

Changes in bund yields at the end of ECB cutting cycles

In all but the 2009 cycle (when aggressive quantitative easing followed interest rate cuts), 10-year bund yields tracked 75 basis points higher, on average, in the 200 days following the last cut.

This cycle, 10-year bund yields are following that pattern, as the blue line in the chart above shows. Short-dated bund yields also rose in previous cycles, but this year they are not tracking as close to the trend.

Supply, meanwhile, is picking up dramatically – adding additional upside risks to longer-dated yields, particularly bunds, which for years enjoyed a scarcity premium.

My belief that German bund yields are likely to move higher (and prices lower) leads me to favour other markets where cuts to date haven’t been substantial, but where they are likely, such as the US and the UK.

How are we positioned in the current environment?

While we believe long-term outperformance through active management is possible through a diligent investment process and discipline, nobody possesses a crystal ball. A well-informed macro view is important; however, I don’t think it’s credible to pretend that forecasting where the global economy will be in three years’ time has been anything short of a crapshoot in recent years.

What we don’t do for the Artemis Strategic Bond Fund is bank on one big macro bet or cluster into one large credit sector position – ours is not definitely an ‘all on red’ approach to fund management.

Where strategic bond funds can add value in our view is by providing investors with a broad allocation to fixed income based on a strategic view of the economic cycle (but also taking into account where the risks lie in the cycle), while relying on expertise of individual managers in their respective asset classes to continually add value through stock selection, as well as a tactical and disciplined rotation of ideas.

In the post-financial crisis environment, doing this was more difficult. Central banks pancaked global bond curves through aggressive quantitative easing programs, while yield-seeking pushed investors into riskier asset classes and ‘yield tourism’ became commonplace.

Today’s environment is markedly different. It is far more suited to stock selection and a tactical approach. Cross-market volatility has returned, shocks are more frequent, and the calming overtures of massive quantitative easing have been replaced by disruptive quantitative tightening. While some might yearn for the previous volatility suppressed regime – I can’t think of anything worse for active management.